|

|

|

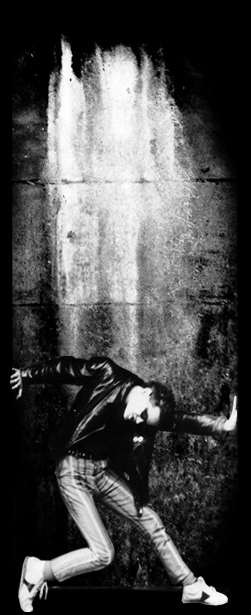

Punk in Western Europe was a pop culture phenomenon with a political background. While on the other hand, Punk in the GDR was a political phenomenon with a pop-culture background. When the first punks showed up in East-Berlin and Leipzig in 1979 it wasn’t the reaction of social and artistic outsiders against a saturated consumer society. Instead it was a reaction against a society of lack, equally underequipped with material goods as well as fundamental freedom. In the GDR it wasn't a matter of family background or unintended social decline that created the outsider, it much more resembled an act of resistance in taking an individual stance in a society which would force everyone into the collective. The punks in the GDR tried to overcome the limitations of a system that strived to control it's young people. They wouldn't let themselves be put under pressure any longer.

This was not only a radicalization of rock n’ roll, but a new form of music and a more emphatic form of artistic expression. Every punk in East Germany risked everything: not only his present situation, but also - for example at 16 years of age - his entire future as well. Along with his family, his school education, his apprenticeship, his occupation, not to mention any chances to attend university. In a “workers and farmers state”, lack of an occupation does not mean a tolerated life on the margins of society, but persecution as an “anti-social element” and frequent imprisonment, to the degree that the repressive measures affected not only the immediate future, but a whole life; the threat to one’s own person was total. In East Germany, a punk rock musician could not build a career as a pop star. An East German punk band played without any prospects of broader, possibly commercial success. It played with the certainty of persecution and the risk of a drastic prison sentence.

The first sightings of Punks invading the bogus ideal of socialism in 1979-1980 can only be compared to the landing of aliens, this is no exaggeration! Stuck in a dead corner of Central Europe the GDR youth was but another human resource for the party officials. A CV would include all the fixed stations of a biography faithful to the system: members in various youth organisations, service in the army, followed by work in socialist manufacturing. If one wasn't manufacturing they were probably studying at the university, which regardless of what one was studying would carry a strong ideological component with it. There wasn't much more to be expected for an average worker or academic. If you weren't delighted about all the forced on "social accomplishments" and not eternally grateful for a secure place in a nursery, a secure training, or secure world peace within heavily secured borders you'd end up experiencing a different kind of security - in a youth detention centre, in a prison, in the army or in the close grip of being under surveillance by the Stasi. The ministry of state security was the system's own symbol for a fetish of security. The over-all social security in the GDR would always be used as a strangling argument against those pointing out the lack of basic human rights. In their corrupt understanding of "give and take" the authorities were taking gratitude for granted that they could no longer expect from the punks.

Too much future, to them, meant no future at all. The initially unfocused attempt to break out (inspired by pop culture and it's more jolly aspects) lead these young people to completely detach themselves from their home country, and would ultimately alter their biographies. In the flashy and flamboyant activities of the punk scene they found a home which the GDR no longer supplied them with. They escaped the country while still living in it, thus becoming free within limits.

Punks appearing in the sheltered world of ‘Real existing socialism’ had to be perceived as unreal and alien in a country that was sealed off from the world, completely unaware of anything foreign. Their care-free and uncontrollable attitude as well as their bizarre appearance (sticking out of the colourful greyness of the East) led to a system being challenged by 16 to 18 year olds, a system that in the long run would become overburdened by it's urge to control. The state's angry response to juvenile anger would leave some of the young people with extreme biographies. That doesn't only include the victims of the GDR dictatorship but also applies to, for example; cases in which 17 year olds - being totally overwhelmed by the critical situation - would be pressured into becoming informers for the Stasi.

Through the oppression executed by a disciplinarian regime, Punk in the GDR would take on an unexpected explosive and society-changing dimension and meaning. The punks in the East would author an eventful chapter of the otherwise leaden GDR history - fascinating for the libertarian excess of their doings, grim and dark for the resulting dimension of their prosecution, whose full force had never been used on any other youth movement before. They did not cause the downfall of the Potemkin state the GDR was rather, they contributed to a nervous balance of the system, which could no longer hold the centre by 1989.

too much future regards itself as an engine behind initiatives examining subculture - especially punk and its repercussions - in the GDR. Since the activities of those involved in the GDR counter-culture didn't stop in November 1989 those repercussions extend beyond the vanishing point. For a lot of activists on the scene their time as punks in the GDR was like a transit space. Their biographies didn't end with them leaving the country or the country leaving itself behind in '89. Instead they continued in various directions and ways of living. Punk for them was a crash course before they landed entirely elsewhere.

Whether in books, in exhibitions or as the topic of a film, the main impulse behind remembering this era is to not to let these biographies become dead letter boxes for history to be discarded in. That involves continuing the narrative beyond its historical context, and exploring the repercussions of Punk in the GDR in the present, even though a lot of it these days exists disconnected from its sub-cultural roots. Even in the years after the wall coming down, A time when bondage turned to total freedom, These repercussions would often reappear in the shape of a certain type of western totalitarian freedom’)

*In official forms "Examination of a circumstance " would always be cited as the reason for Punks being called in for interrogation

|